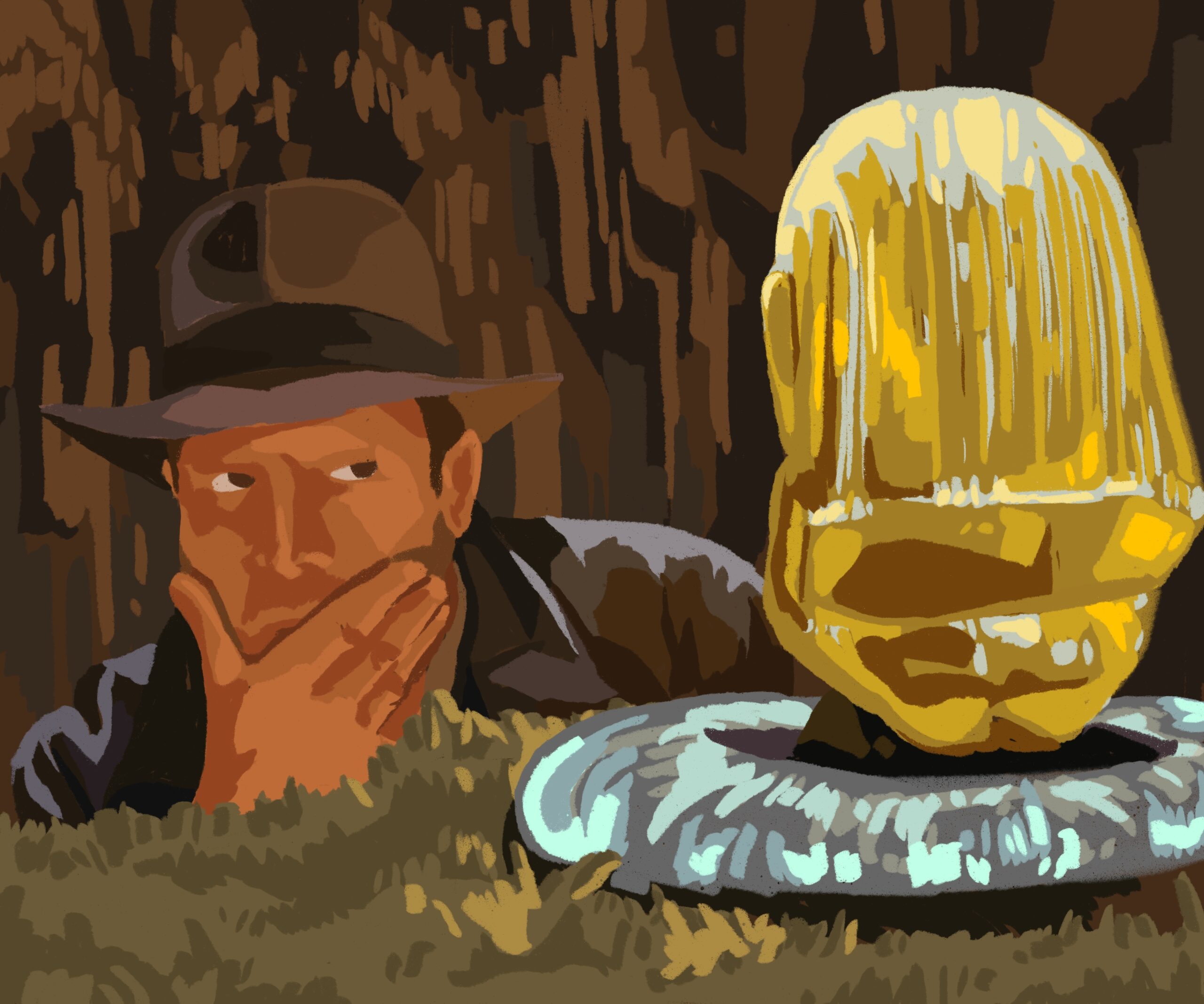

Written by Zach Salter. Illustration header courtesy of Bella Gallegos (@Byebyebellla)

Steven Soderbergh made an enormous splash in the film industry in 1989 when his debut feature, “Sex, Lies, and Videotape,” won the prestigious Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. He was only twenty-six years old at the time, but his impact on the independent filmmaking scene was remarkable – and today, it’s only made even more impressive by the wildly-varied oeuvre of movies that he’s directed since. With Soderbergh’s newest film, “Black Bag,” on the horizon (releasing on March 14 in the United States), now is a better time than ever to revisit one of the prolific filmmaker’s most unique and surprising achievements – his 2014 cut of “Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

That 1981 film is the definition of a classic – memorable not only for its exhilarating action set-pieces, endlessly hummable John Williams score and charismatic lead performance from Harrison Ford – but also for its effortlessly efficient direction from Steven Spielberg, who could honestly be described as an auteur of classics. The brilliance of the film certainly warrants a question: What could a new cut possibly add to the experience? Soderbergh’s answer doesn’t come with additions or enhancements, but rather, with subtractions. On his “Soderblog,” he presents a version of the film devoid of both its color and original sound (which he substitutes for a soundtrack by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross), designed to accentuate the film’s staging – which Soderbergh describes as “how all the various elements of a given scene or piece are aligned, arranged, and coordinated.”

Take the prologue, for instance, which now kicks off with Reznor and Ross’ “In Motion” (from their original score for “The Social Network”) and a beautiful, monochromatic variant of that satisfying transition from the Paramount logo to the opening shot’s mountainous landscape. By creating a mental separation between the film’s audio and visual elements within the viewer, Soderbergh provides an experience that allows one to closely appreciate Spielberg’s masterful blocking. It may be obvious on a viewing of the original cut that Ford’s face doesn’t appear until over three minutes in, but one may not notice the clever use of depth that Spielberg employs in showing his character beforehand. In one shot, Ford’s hands emerge from the lower left and hold a map up in the foreground – but Alfred Molina (Satipo) stands in the middle of the background, watching him in anticipation. With a frame like this, Spielberg efficiently provides both an action and a reaction, but also crafts a visual that builds a sense of mystery and intrigue surrounding his obscured character.

It’s the little details like this that Soderbergh brings to lustrous, black and white light in his revelatory cut of “Raiders” (as he funnily dubs it – plundering the title of most of its words to match his removal of much of the film’s content). Over his thirty-plus-year career, he’s clearly dedicated himself to exploring his own, broad filmmaking skills, through a series of films that cover all genres, but this experimental effort of his stands as one of his most memorable works yet – one which is also dedicated to exploring great, cinematic mastery – or as Soderbergh puts it: that “high level visual math shit.”